My parents told me I was too poor to buy into the Richardson family medical practice on the same week I signed the papers to acquire it through the hospital I ran.

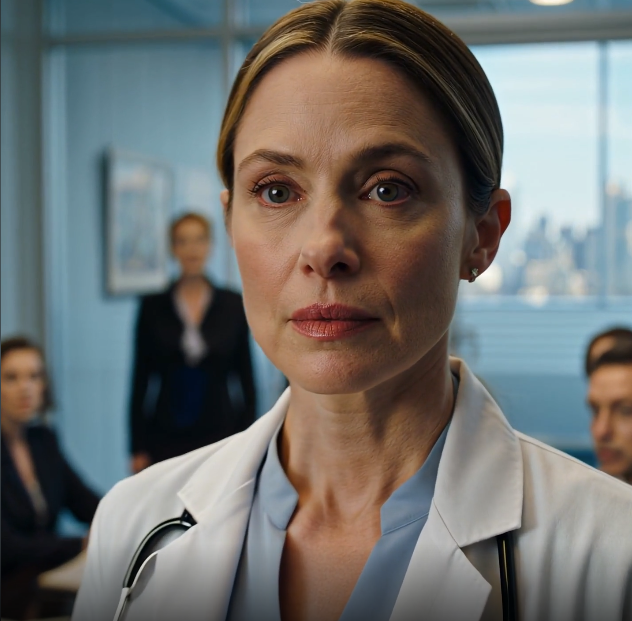

They sat across from me in a high-floor conference room at Memorial Hospital, the Chicago skyline framed behind my shoulders like a quiet chorus. My father’s hair was completely silver now, my mother’s pearls were the same ones she’d worn to every graduation and awards dinner. They were both still so sure of who they were and who I was supposed to be.

“Even if you had the training,” my father said, his tone clipped, “you could never afford a serious stake in this practice, Cheryl. You don’t understand the scale we’re talking about.”

He had no idea he was talking to the chief executive officer and chief medical officer of the very hospital that had already bought him.

It had taken me fifteen years to get to that table.

My name is Cheryl Richardson. I grew up in an affluent suburb outside Chicago where the Richardson name was synonymous with medicine. People didn’t just say, “I’m going to the doctor.” They said, “I’m seeing the Richardsons.”

My grandfather had built the original clinic after World War II. My father, Dr. James Richardson, turned it into a thriving internal medicine practice. My mother, Dr. Margaret Richardson, expanded it with obstetrics and gynecology. Between them, they’d delivered half the town and kept the other half alive long enough to be grateful for it.

By the time I was five, neighbors were already talking about “the next generation of Dr. Richardsons.” They meant my older brother, Thomas. They assumed I would follow along.

In our house, medicine wasn’t a career. It was the family religion.

My bedroom walls didn’t have movie posters or boy band photos. They had laminated anatomical charts and framed copies of my parents’ diplomas. Toy doctor kits appeared under the Christmas tree every year. At dinner, my father quizzed us on anatomy while my mother described complicated deliveries between bites of roast chicken.

“Medicine is in your blood, Cheryl,” my father would say, topping off his iced tea.

“The Richardson name carries responsibilities,” my mother would add, like a line from Scripture.

Thomas absorbed it all like oxygen. Four years older than me, he was the kind of son that made other parents jealous. Handsome, charming, good at chemistry. He shadowed our parents at the clinic in high school and came home glowing, full of stories about elderly patients and cute toddlers.

“Thomas understands what it means to be a Richardson,” my mother liked to say.

She didn’t have to finish the sentence for me to hear the rest.

I tried. I really did.

When I was sixteen, my parents put me at the front desk of Richardson Family Medicine for the summer. The practice occupied the top two floors of a glass and steel medical building my grandfather had built, with marble floors in the lobby and a wall of donor plaques that all shared our last name.

I answered phones, checked in patients, filed charts. I learned who liked the early-morning appointments and who always arrived ten minutes late. I watched my father stride down the hallway in his white coat, stethoscope slung around his neck like a badge of office. I watched my mother come back from deliveries, tired but radiant.

I loved the feeling that what we were doing mattered. I loved watching patients walk in anxious and leave reassured.

But what caught my eye wasn’t just the exam rooms.

It was the scheduling system, a mess of color-coded blocks and handwritten notes. It was the billing office crammed with filing cabinets, the practice manager on the phone arguing with an insurance company about a denied claim. It was the monthly staff meeting where my father sighed about shrinking reimbursements and rising costs.

I found myself fascinated by the machinery behind the medicine, the systems that made it all possible—or impossible.

During my senior year of high school, I had the chance to shadow the administrator at the local hospital for career day. While my friends followed surgeons and ER nurses, I followed a woman in a navy suit through budget meetings and planning sessions.

We walked through the emergency department while she talked about throughput and staffing ratios. We sat in a conference room while physicians argued about adding a new clinic on the south side of town. She showed me spreadsheets, dashboards, and patient satisfaction graphs.

It should have been boring.

It wasn’t.

For the first time, I saw the whole organism—how one policy decision could ripple through thousands of lives. It felt like discovering a new layer of medicine no one in my family ever talked about.

I went home that night lit up with ideas. I wanted to redesign the clinic waiting room. I wanted to streamline the appointment system. I wanted to make the whole thing work better, not just for the doctors, but for the patients and staff.

I almost told my parents.

Then I pictured my father’s face, the way his jaw tightened whenever someone mentioned “administration,” like it was a necessary evil. I pictured my mother’s polite smile when she talked about hospital meetings.

So I kept it to myself.

Instead, I did what they expected. I applied to the premed programs my father circled in brochures. I wrote essays about my dream of becoming a doctor “like my parents and my brother.” I accepted a spot at my father’s alma mater, a prestigious private university with a notoriously brutal premed track.

When I left for college, my parents hugged me like they were handing off a relay baton.

“First step to becoming Dr. Richardson,” my mother said.

It took almost three years for me to admit that I didn’t want that step to lead to the exam room.

By junior year, I had survived organic chemistry, endless labs, and more multiple-choice questions than I cared to remember. I was doing fine on paper. My grades were solid, my MCAT prep on schedule.

But every time I imagined my future, it wasn’t the image of me in a white coat that kept me going. It was the image of me in a boardroom, redesigning how care was delivered.

One chilly March weekend, I took the train home for spring break with that realization buzzing under my skin.

My parents insisted on a formal family dinner my first night back—linen napkins, the good china, a roast that smelled like every major family announcement of my life.

I pushed peas around my plate as my father described a complicated cardiac case and my mother chimed in with a story about a high-risk delivery. Thomas, now in his second year of medical school, added his own anecdotes, and they laughed like colleagues.

I listened and felt like I was outside a glass wall watching someone else’s family.

“Mom, Dad,” I said finally, heart pounding against my ribs. “There’s something I need to talk to you about.”

Both of them went still. Even Thomas’s fork froze halfway to his mouth.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about my future,” I said. “About medicine. I don’t want to go to medical school. I want to go into healthcare management and administration. I want to work on the systems that make care possible.”

The silence that followed was immediate and suffocating.

My father set his fork down very carefully.

“That is not medicine,” he said, his voice low. “That is paperwork. Richardsons are healers, not paper pushers.”

“Dad, administrators design the systems that let doctors practice,” I said, words tumbling out. “They decide where clinics go, what programs get funded, how patients move through the hospital. They can affect outcomes on a scale no single physician—”

“Enough,” he snapped, his palm hitting the table hard enough to rattle the glasses. “This is about you lacking the discipline for medical school. You’re looking for an easy way out.”

My mother’s disappointment cut even deeper.

“We have invested everything in preparing you for medical school, Cheryl,” she said. “The connections we’ve used, the letters we’ve lined up. Do you have any idea how many people would give anything for the opportunities you’re throwing away to become some kind of glorified secretary?”

“It’s not a secretary job,” I said, heat rising in my face. “It’s leadership. Hospitals need—”

“What hospitals need,” my father interrupted, “are competent physicians. Not more administrators telling us how to do our jobs.”

The argument spiraled from there—old resentments, sharp words I wished I could take back, accusations I had dreaded hearing voiced out loud.

By the time the roast grew cold and the candles burned low, my father looked at me like he was issuing a verdict.

“If you walk away from medical school,” he said, “you do it without our support. Not one more dollar. The Richardson legacy is not something you dabble in until it gets hard.”

My mother’s eyes were bright with angry tears.

“You’re not just betraying us,” she whispered. “You’re betraying generations of Richardsons who built this name.”

That night I lay awake in my childhood bedroom, the familiar outlines of my life pressing in on me. Anatomy posters. A bookshelf of MCAT prep books. A white coat my parents had given me in high school as a “preview” of my future.

In the morning, before anyone else was up, I packed my bag, left a note, and took the first train back to campus.

At twenty years old, I walked into the financial aid office and told the woman behind the desk that my tuition check wasn’t coming.

They cut me off. Completely.

I signed emergency loans with a shaking hand. I took on every campus job I could—library aide at dawn, dining hall shifts in the evening, lab assistant at night. I counted every dollar, skipped meals, and studied in between.

Holiday visits home became short and careful. We talked about the weather, about random family gossip. We did not talk about my major. Thomas tried to play peacemaker from a safe distance.

“They just want what’s best for you,” he said once over the phone.

“What’s best for me,” I answered, “is not living a life I don’t want.”

If their rejection hurt, it also hardened my resolve.

I switched my major to healthcare management, added a business concentration, and attacked my new coursework with something close to ferocity. Health policy, organizational behavior, finance—they made sense to me in a way organic chemistry never had.

My grades, already good, became exceptional.

During my senior year, I met the person who would change everything for me.

Her name was Dr. Eleanor Winters, CEO of a regional hospital network and a visiting lecturer for a healthcare innovation seminar. She had the calm authority of someone who’d walked into a lot of rooms full of skeptical men and walked out with the decision she wanted.

Halfway through a lecture on emergency department crowding, she asked for ideas. I raised my hand and laid out a reworked triage model and fast-track system I’d been sketching in my notebook for weeks.

After class, she asked me to stay behind.

“You have a rare perspective,” she said. “You understand both the clinical language and the administrative one. That combination is powerful.”

I told her about my family, about the dinner where my father called my chosen path lazy and my mother called it betrayal. I braced for judgment.

Instead, she nodded.

“There are a lot of people in healthcare who think the only honorable role is the one in the white coat,” she said. “They’re wrong. Systems save lives, too. Sometimes more lives than any single doctor ever could.”

She became my mentor.

With her help, I landed a competitive internship at a local hospital. For the first time, I worked beside administrators who saw value in my ideas. I designed a pilot intake redesign for the emergency department. Wait times dropped. Patient satisfaction climbed.

It felt like proof—not that my parents were wrong, but that I wasn’t.

I went on to grad school, pursuing a dual master’s in healthcare administration and business. I lived on cheap coffee and secondhand furniture, worked as a graduate assistant, and stacked loans like bricks under my feet.

Every semester, I mailed my transcript home.

Sometimes they sent a short note back: “Congratulations on your grades. Love, Mom and Dad.”

Nothing more.

After graduation, I accepted an administrative fellowship at Memorial Hospital, a three-hundred-bed teaching hospital in the city, three hours from my hometown. The fellowship was designed to groom future leaders. It rotated us through departments, paired us with mentors, and dumped real problems in our laps to see what we did with them.

I thrived.

I wasn’t the smartest person in every room anymore, but I was often the one willing to ask the uncomfortable question.

Why are we doing it that way? What does the data actually say? How does this decision land in the waiting room, not just the boardroom?

My capstone project was a redesign of the outpatient scheduling system. Within a year, no-show rates had dropped by nearly a third and revenue had climbed by a couple million dollars.

“You see the forest and the trees,” the chief operating officer told me. “We need people like you in leadership.”

When the fellowship ended, Memorial offered me a job as director of outpatient services. From there, the promotions came slowly, then all at once.

I became associate COO at thirty, chief operating officer at thirty-three.

Older physicians didn’t always like taking orders from a young administrator who hadn’t completed a residency. Some dismissed me as “the suits upstairs,” even when I was standing right in front of them. I learned to let data and consistency do the arguing.

We rolled out electronic health records, revamped clinics, and launched community programs in neighborhoods my parents’ patients rarely thought about. We opened free evening clinics, set up school-based health education, and partnered with churches for blood pressure screenings.

In the process, I developed a reputation: tough on budgets but fiercely protective of patient care and staff well-being.

My personal life, meanwhile, was quieter. I dated a little, nothing that survived my schedule. My closest friend became Michael Carter, the hospital’s in-house legal counsel—a sharp, dry-humored attorney who understood exactly how a single misstep could blow up months of careful planning.

“Someday you’re going to be running this place,” he told me after one especially brutal contract negotiation.

I laughed it off.

Then, when I was thirty-six, the CEO announced his retirement.

The board encouraged me to apply. So did Michael. So did Dr. Winters, who had stayed in my life with the tenacity of someone used to mentoring stubborn people.

The interview process was grueling. Presentations, stakeholder meetings, endless questions about my age.

In the end, the board voted. When the chair called to offer me the position of chief executive officer and chief medical officer of Memorial Hospital, I was sitting alone in my office, staring at a whiteboard full of unfinished projects.

I remember hanging up the phone and just listening to the hospital sounds around me. The overhead pages. The murmur of voices in the hallway. The squeak of a cart rolling past.

I had become, in my own way, exactly what my parents had always wanted: someone whose work shaped the health of an entire community.

They just didn’t know it.

I told Michael. I told Dr. Winters.

I did not call home.

“They still think I’m pushing paper somewhere,” I told Dr. Winters over the phone. “If I call to say I’m running a hospital, it’ll sound like I’m trying to win an argument from fifteen years ago.”

“Then don’t call for them,” she said gently. “Call when you’re ready for you.”

I didn’t. Not then.

My first year as CEO was a blur of crises and victories—an electronic records rollout that nearly mutinied, a national quality review that ended with us winning an award, a hundred smaller fires that never made the news but kept me up at night.

It was during a strategic planning retreat with my executive team that my past and present collided.

We were in a generic hotel conference room near O’Hare: beige carpet, humming air conditioner, whiteboards full of bullet points. Jessica Lawson, our chief strategy officer, stood at the front of the room with a spreadsheet projected behind her.

“As part of our five-year growth plan,” she said, “we’ve identified fifteen independent practices that might be candidates for acquisition or affiliation. Most are primary care. Some are specialty groups looking for stability in a changing reimbursement landscape.”

I sipped lukewarm coffee and skimmed the list.

About halfway down, my heart stuttered.

Richardson Family Medicine.

I stared at the words, half convinced I was imagining them.

“What’s the story with this one?” I asked, keeping my voice level.

Jessica tapped her tablet, pulling up another slide.

“Strong brand recognition, long history in their community, a patient panel that skews older but loyal,” she said. “Financially, they’re…interesting.”

“How interesting?”

“They’re still profitable, but their overhead is high. They’ve resisted fully implementing an electronic health record, their billing is outdated, and they’ve made some questionable equipment purchases. They’re cash-rich but operationally inefficient. And younger patients are drifting to newer, more modern practices in town.”

I felt a laugh bubble up, too sharp to let out.

The very skills my parents had dismissed—the business and administrative expertise they’d treated as beneath the dignity of a Richardson—were exactly what their legendary practice now lacked.

I excused myself after the presentation and went back to my office.

My first instinct was to recuse myself completely. To tell the board I couldn’t touch anything with my family’s name on it. To pretend this was just another practice on a list.

My second instinct—the one fueled by a twenty-year-old sitting at a dining table being told she was throwing her life away—wanted to sit in every meeting, sign every page, and make sure the story played out on my terms.

I called Michael.

“So,” he said after I finished explaining. “Your hospital is about to buy your parents’ practice.”

“Looks that way,” I said.

We ran through the legal and ethical considerations. As long as the acquisition made sense on its own merits, as long as I disclosed my conflict to the board and allowed extra oversight, I was within bounds.

“What do you want to do?” he asked finally.

“I want the deal to be good business,” I said. “If their last name wasn’t mine, we’d still want that practice. And…I want to be the one who faces them.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“Then we’ll build the guardrails and you’ll walk through the fire,” he said. “Seems on brand.”

The due diligence process on Richardson Family Medicine confirmed everything Jessica had said and more.

Their refusal to modernize had made them a museum of medicine rather than a leader. Their compensation model heavily favored senior partners—my parents—while younger doctors left as soon as they could. Their patient satisfaction scores, once stellar, had slipped as wait times grew and communication faltered.

The acquisition committee, seeing the practice as both a risk and an opportunity, recommended moving forward. The location, the brand, the long-term relationships—they were still worth something. Under better management, the practice could thrive.

The recommendation came to my desk. I signed it.

In a typical acquisition, I would have stayed mostly in the background, letting Jessica and our integration team handle the details.

This time, I didn’t.

“I want to lead the integration for Richardson Family Medicine personally,” I told Jessica during our next one-on-one.

She looked surprised.

“With your schedule?” she asked. “You don’t usually get involved at that level.”

“This practice is different,” I said. “It has outsized influence in its community. I want to make sure we get it right.”

I didn’t tell her the rest—that I needed to sit across from my parents as the person I had become, not the daughter they remembered.

We set the first joint meeting for a Tuesday morning. At my request, the invitation went out from Jessica’s office to “Memorial Hospital Leadership.” There was no mention of my name.

The morning of the meeting, I stood in the small bathroom off my office, smoothing my suit jacket and applying a final swipe of lipstick. At thirty-eight, I barely resembled the college student who’d fled home with a duffel bag and a stack of loan forms, but my stomach still knotted like it had then.

“They’re not going to recognize you,” Michael said from the doorway. “Not just the hair and the suit. You.”

“That’s kind of the point,” I said.

He hesitated.

“I can still take this one,” he offered. “You don’t owe them a dramatic reveal.”

“I don’t,” I agreed. “But I owe it to myself.”

The executive conference room on the hospital’s top floor had floor-to-ceiling windows and a long table that had seen more high-stakes conversations than anyone could count. When I walked in, there were five people already seated at the far end.

My father. My mother. Thomas. Two younger doctors I didn’t recognize.

My father looked older, the lines around his mouth and eyes deeper, but his posture was still rigid. My mother’s hair was perfectly styled, pearls at her throat, reading glasses on the table beside her. Thomas looked like a slightly younger version of our father, right down to the folded arms.

For a moment, they didn’t look up, absorbed in the documents in front of them.

“Good morning,” I said, closing the door. “Thank you all for coming.”

Five heads lifted.

Shock registered almost comically clearly. My mother’s hand flew to her collar. Thomas’s mouth literally fell open. The younger physicians glanced between us, sensing drama without context.

“Cheryl,” my mother breathed.

I set my portfolio on the table and took the seat at the head opposite them.

“Dr. Richardson,” I said. “Chief executive officer and chief medical officer of Memorial Hospital.” I let the words hang there. “It’s good to see you.”

My father’s face tightened.

“What is this?” he demanded. “Some kind of joke? Where is the administrator we were told we’d be meeting with?”

“You’re looking at her,” I said evenly. “I’ve been at Memorial for fifteen years, the last eighteen months as CEO. Today we’re here to discuss the acquisition of Richardson Family Medicine by our hospital network.”

“This is outrageous,” he said, half-rising from his chair. “We agreed to a professional meeting, not some family ambush.”

“This is a professional meeting,” I said. “Your practice approached our team about joining our network. As CEO, I’m responsible for all final acquisition decisions.”

I kept my tone cool, my eyes steady.

“We can proceed now,” I added, “or we can reschedule for another time when you’re more comfortable. The business realities will be the same either way.”

That landed.

He slowly sat back down.

“Let’s get this over with,” he muttered.

For the next ninety minutes, we went through the numbers. I presented the data the way I would to any other practice: referral patterns, payer mix, overhead, patient satisfaction.

“Over the past five years,” I said, gesturing to a graph on the screen, “Richardson Family Medicine has seen a twenty-eight percent decline in new patient growth, while operating expenses have risen thirty-five percent. Your accounts receivable cycle is nearly twice the industry standard. Partial EHR implementation has created inefficiencies without delivering full benefits.”

My mother flinched at each negative metric. My father’s jaw clenched tighter.

“Our practice has delivered exceptional care for decades,” he snapped at one point. “These business metrics don’t capture that.”

“Patient satisfaction scores capture part of it,” I said. “Yours have declined six consecutive quarters. None of this negates the good you’ve done. It just means the systems around your clinical work aren’t keeping up.”

Eventually we came to the offer.

“Based on our analysis,” I said, “Memorial is prepared to purchase the practice for the following amount and terms.”

I laid out the number. It was fair. Not inflated by nostalgia, not punitive. Just real.

One of the younger doctors nodded slowly.

“This seems reasonable,” he said.

Thomas cleared his throat.

“Given where we are financially, it’s…in line with what I’ve been seeing,” he said carefully.

My father shot him a look sharp enough to draw blood.

“It’s insulting,” he said. “You’re undervaluing decades of reputation and goodwill. You’re treating us like some failing strip-mall clinic.”

“The offer reflects current performance and market conditions,” I said. “We also place value on the Richardson name and history, which is why we’re proposing to retain the practice name and your leadership for a transitional period.”

“A transitional period,” he echoed. “So you can push us out of our own practice when it suits you.”

“That’s standard,” I said. “But we’re open to structures that work for everyone, as long as they align with our quality and operational standards.”

He leaned back, eyes narrowing in a way I knew too well.

“Perhaps there’s another way to structure this,” he said. “Instead of a full acquisition, your hospital could bring in a partner to update our operations while we retain independence.”

My spine stiffened.

“And who would that partner be?”

He gestured toward me, his expression shifting into something that might have passed for magnanimous if I didn’t know him.

“Well,” he said, “it seems my daughter has picked up some administrative skills. Perhaps she could buy into the practice. A twenty percent stake, to start. She could try out her corporate ideas, and we’ll maintain clinical control.”

I stared at him.

It was almost impressive, the way he could pivot so quickly—turning my entire life into a tool to avoid a full acquisition.

“Are you offering me a position in the family practice, Dr. Richardson?” I asked, my tone neutral.

“It seems like the natural solution,” he said with a shrug. “You finally join the Richardson medical tradition, we gain from your experience. Everyone wins.”

“And what would the buy-in cost?” I asked.

He named a number. It was high enough that one of the younger physicians blinked.

It didn’t matter. He clearly didn’t believe I could afford it, not on a “paper pusher’s” salary.

“That’s an interesting proposal,” I said, letting a quiet beat stretch. “But I think you may be misunderstanding my position and resources.”

He waved a hand.

“I realize the figure might be beyond your means at the moment,” he said. “Perhaps the hospital could structure it into your compensation package.”

The condescension in his tone was the final click of some internal lock.

Fifteen years of being dismissed. Fifteen years of being treated as though my choices made me smaller, not different.

I opened my laptop and pulled up a document I’d had ready since the board vote.

“Actually, Dr. Richardson,” I said, turning the screen toward him, “there are a few misconceptions we should clear up.”

“First, as chief medical officer of Memorial, my clinical privileges are broader than anything your practice could offer. Second, as CEO, I don’t need to buy into your practice.”

I slid a printed copy of the document across the table.

“Memorial Hospital already owns it.”

He stared at the paper.

“That is the preliminary acquisition agreement your practice administrator signed last week,” I said. “Your board has already voted to accept our offer. This meeting isn’t about whether Memorial will acquire Richardson Family Medicine. That decision has been made. We’re here to discuss how the transition will work.”

The color drained from his face.

My mother’s hand flew to her mouth. Thomas looked back and forth between us like he was watching a building he’d always assumed was solid start to crack.

“As of next month,” I continued, “Richardson Family Medicine will become a wholly owned subsidiary of Memorial Hospital. As CEO, I’ll have final authority over operational decisions, including staffing and compensation.”

I closed my laptop with a quiet click.

“Now,” I said, “we can talk about how you’d like to fit into that structure—or not.”

The meeting imploded soon after.

My father stood up so fast his chair tipped.

“You set us up,” he said, voice shaking with fury.

“No,” I said. “I treated your practice like every other one we evaluate. If anything, I added extra oversight to avoid favoritism.”

He didn’t answer. He just left, my mother following quickly, one last conflicted look cast over her shoulder.

The two younger physicians stood, clearly shell-shocked.

“We’ll reconvene tomorrow,” I told them. “Once everyone has had a chance to process. My team will reach out.”

They nodded and slipped out.

Thomas lingered.

For a moment, we just looked at each other—the golden son who’d stayed, the black sheep who’d left.

“So,” he said finally, a faint, disbelieving smile tugging at his mouth. “This is what you’ve been doing all these years.”

“I built a career,” I said. “Just not the one they picked for me.”

“Are you doing this to get back at them?” he asked quietly. “Buying the practice, sitting at the head of the table—was this about revenge?”

The question sat between us. I thought about that jolt of satisfaction when my father realized who I’d become, when the power dynamic flipped for the first time in our lives.

“Revenge would’ve been letting the practice keep sliding until it collapsed,” I said. “Letting their refusal to change destroy everything they built. This acquisition makes sense. The brand still has value. The patients deserve better systems. So do the staff.”

He nodded slowly.

“They’re never going to see it that way,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “But that’s kind of the story of our family, isn’t it? They see what they expect, not what’s in front of them.”

We parted with a brief, awkward hug. He promised to talk to our parents, to try to get them to come back to the table.

The next morning, my assistant buzzed my office.

“Your parents are in the lobby,” she said. “They’re asking to see you.”

I had them shown to a smaller, more private conference room.

They looked drawn when I walked in, like neither of them had slept much.

“We’ve come to discuss terms,” my father said, voice stiff. “Since it appears the acquisition is unavoidable.”

“There are always options,” I said. “But yes, the acquisition is proceeding. The question is whether you want to be part of the new structure or retire.”

My mother flinched at the word retire.

“If we stay,” my father asked, “are you planning to…punish us? For the past?”

There it was. Not an apology. Not yet. But an acknowledgment that there was a past, and it had weight.

“What happened between us is personal,” I said. “What I’m doing with the practice is business. The changes I’m going to make—full EHR implementation, centralized billing, new compensation models—are what I would do with any practice in your position.”

I held his gaze.

“If you’re asking whether I’m going to use my position to get back at you, the answer is no,” I said. “That would be unprofessional and bad for the hospital. But I’m also not going to protect outdated systems because we share a last name.”

My mother’s eyes were wet.

“You’ve changed,” she said softly. “You’ve become so…hard.”

“I’ve become effective,” I replied. “I built something that takes care of thousands of patients every day. And I did it without the support of the people who should’ve been my biggest champions.”

The cracks showed in her composure.

“Perhaps,” she said, “we were wrong about some things.”

My father shifted uncomfortably.

“Your brother showed us some articles last night,” he said gruffly. “Awards. Programs you’ve started. They were…impressive.”

It wasn’t an apology. But for my father, it might as well have been.

“Thank you,” I said.

We spent the next two hours working, really working, through the transition.

They were worried about their long-term patients, about staff who’d been with them for decades, about losing their identity. I listened. Where their concerns fit good medicine and sound operations, I built them into the plan. Where they were about ego, I didn’t.

We agreed they would stay on for two years, gradually reducing their patient loads while younger physicians took on more leadership. Thomas would remain as a senior physician but would also start training in administrative leadership inside Memorial’s primary care division.

As we wrapped up, my mother hesitated.

“Will you come to dinner sometime?” she asked. “Not to talk about business. Just…dinner. With family.”

Fifteen years of distance and hurt hung between us.

“I’m not ready for that yet,” I said. “Maybe someday. But not yet.”

She nodded, accepting the boundary in a way she wouldn’t have when I was twenty.

My father stood and held out his hand.

“Dr. Richardson,” he said.

“Dr. Richardson,” I answered.

The months that followed were a blur of renovation and redesign.

We refreshed the practice physically—lighter paint, better lighting, a waiting room that didn’t feel like a time capsule from the early nineties. We modernized workflows and brought in scribes to help older doctors adjust to the electronic record.

I made a point of meeting every staff member one-on-one.

Many of them had known me as a teenager at the front desk. They’d heard a version of the story where I “walked away from medicine.”

“I never walked away from medicine,” I told one longtime nurse, a woman who’d been there since before I could spell stethoscope. “I just found my way to a different part of it.”

One of the younger physicians, Dr. David Kim, sat across from me with a weary expression.

“I was planning to leave,” he admitted. “Your parents shot down every suggestion for improvement. Every time I mentioned changing something, they said the ‘Richardson way’ was the only way.”

I smiled at the phrase that had defined my childhood.

“Well,” I said, “there’s about to be a new Richardson way. I’d like you to be part of building it.”

He stayed.

As the practice improved—shorter wait times, better communication, higher staff morale—my parents began to relax their grip.

My father still grumbled about “bureaucracy,” but he also started asking for patient satisfaction reports without being prompted. My mother volunteered to lead a new women’s health outreach program for uninsured patients, something she never would’ve had time or inclination for in the old model.

Thomas and I, for the first time, became true collaborators.

He respected my ability to make the numbers work. I respected his ability to sit with a terrified patient and make them feel safe.

We still clashed—over resource allocation, over priorities—but we clashed as equals.

A year after the acquisition, we hosted an open house at the newly renovated practice.

The waiting room was packed with patients, staff, and community leaders. The old oil painting of my grandfather’s hunting lodge had been replaced with a large photograph collage of the town: the high school, the park, the church steeples, the hospital.

My father stood at a small podium, looking out over a sea of faces that had known him for decades.

“For over thirty years,” he said, “I believed there was only one right way to practice medicine—the Richardson way.”

A murmur of laughter moved through the crowd. Everyone knew what that meant.

“What I failed to see,” he continued, “was that the Richardson way could change. That it had to change.”

He looked up and found me at the back of the room.

“Sometimes,” he said, “it takes a new generation to show us what we’ve been missing.”

It wasn’t a grand confession. But it was something real, offered where it mattered—in front of the people whose opinions had always mattered so much to him.

Afterward, my mother found me near the refreshment table and handed me a glass of sparkling water.

“Your father may never say it the way you want to hear it,” she said. “But he’s proud of you. We both are.”

“Even though I never became a doctor?” I asked.

She smiled, a little sadly.

“You became exactly what this family needed,” she said. “We were just too stubborn to see it.”

Later that night, after the crowd thinned and the staff started cleaning up, I stepped into what used to be my father’s private office.

The heavy mahogany desk was gone, replaced by a round table and a few chairs. The room felt less like a throne and more like a workspace.

Thomas leaned against the doorway.

“Quite a journey,” he said. “From being told you were too poor to buy into the practice to owning the hospital that owns the practice.”

I laughed softly.

“That was never the goal,” I said.

“Wasn’t it at least a little bit?” he asked.

I thought about that first meeting in the conference room, the look on our father’s face when he realized who I’d become.

“Maybe, for a moment,” I admitted. “Seeing his expression—that was…satisfying. But it faded faster than I expected.”

“What replaced it?” Thomas asked.

“Understanding that if I spent my life trying to prove them wrong, I’d still be letting them define me,” I said. “Real freedom came when I built something that mattered to me, whether they approved or not.”

He studied me for a long moment, then nodded.

“I followed the plan they laid out,” he said. “I never questioned it. You walked away from it with nothing but loans and stubbornness. I’m not sure which one of us had the harder job.”

“Different kinds of courage,” I said. “Different kinds of scars.”

In the months that followed, my family and I kept figuring it out.

We were never going to be the kind of people who said “I love you” over every phone call or cried together at sentimental commercials. But my father started calling me to ask for advice about investments and staffing decisions. My mother and I began meeting for lunch once a month, conversations drifting slowly from safe topics into something like real relationship.

One afternoon, after a leadership seminar at Memorial, a young administrative intern approached me, clutching a notebook.

“Dr. Richardson?” she said. “My mom was your father’s patient for years. He told me I should talk to you about going into healthcare administration. He said you were the best mentor I could have.”

For a second, I couldn’t speak.

The man who had once slammed his hand on a dining table and called my chosen path an embarrassment was now sending young people to me because he believed in what I did.

That was a kind of healing I hadn’t even known I wanted.

The journey from rejection to respect wasn’t neat. There were no sweeping apologies, no weepy movie-scene reconciliations. There were awkward pauses, old wounds that ached when pressed, and new mistakes layered on top of old ones.

But there was also something sturdier than the approval I’d once begged for.

There was the knowledge that I had built a life that aligned with who I was, not who someone else thought I should be. There was the quiet pride of seeing systems run better because I refused to believe that only the person in the white coat mattered.

My parents once told me I was walking away from everything that mattered when I chose hospital administration over medical school. They told me, in every way they knew how, that my work would never hold the same weight as theirs.

They were wrong.

But the real victory wasn’t proving them wrong.

The real victory was realizing that their approval was never the measure of my worth in the first place.

Today, when I walk through the halls of Memorial or step into the renovated lobby of Richardson Family Medicine, I hear echoes—of my father’s pronouncements, of my mother’s warnings, of my own fear.

I also hear something else.

Nurses laughing. Patients being called back on time. A receptionist explaining a payment plan that actually makes sense. A young administrator I’m mentoring pitching an idea in a meeting with the kind of shaky bravery I remember so well.

Legacy isn’t just the name on the door or the degrees on the wall.

It’s the systems you build, the people you lift up, and the courage to step off a path that was never really yours and make something better in its place.

My parents once said I was too poor to buy into their world.

In the end, I didn’t buy in.

I built my own, and then I opened the door wide enough for all of us to walk through.