Before he could explain, she came back into the room, one hand clenched tightly around her leather purse.

I never imagined that after sixty-three years of living a quiet Midwestern life, I would find myself sitting in a neurologist’s office at the University Hospital in Iowa City, my heart pounding with a fear I didn’t yet understand.

My name is Kathy Cuban, and for the past four years, I’ve watched my husband, Steven, slip away from me piece by piece. Not through death—that might have been easier to accept—but through the cruel fog of memory loss that settled over his mind like winter frost on our Iowa farmhouse windows.

Steven was seventy when it started. Small things at first. Forgetting where he’d left his reading glasses. Repeating the same story twice in one evening at Sunday dinner. Calling our grandson by our son’s childhood name.

I told myself it was normal aging. We all forget things.

But then came the morning he couldn’t remember how to start the John Deere tractor he’d driven for forty years, the same green machine that had plowed our three hundred acres of prime Iowa soil through droughts and bumper crops alike. That was when I knew something was terribly wrong.

Our daughter, Clare, insisted we see specialists.

She drove up from Des Moines every few weeks in her shiny crossover SUV, her designer heels clicking across our old pine floors, her perfume—something expensive and floral—filling rooms that usually smelled like coffee, wood polish, and old books.

She meant well, I told myself. She was worried about her father.

But there was something in her eyes during those visits that I couldn’t quite place. A calculation. A quiet measuring.

She would walk slowly through the farmhouse, built by Steven’s grandfather in 1889, and look out across the rows of corn and soybeans like she was appraising them. I caught her more than once taking photos of the antique furniture with her phone, lingering over the walnut sideboard that had belonged to Steven’s mother.

She asked casual questions about the property deed, whether the land was fully paid off, whether we had any liens.

“Mom, you’re both getting older,” she’d say, squeezing my hand with perfectly manicured fingers. “We need to be practical. Have you thought about power of attorney? What happens if you can’t make decisions for Dad?”

I always changed the subject. Something about those conversations made my skin crawl, though I couldn’t explain why.

Clare was our older child. Who else would we trust?

Last Tuesday changed everything.

Clare had scheduled an appointment with Dr. Michael Hartley, a neurologist at the university hospital in Iowa City. She’d been pushing for this evaluation for months, and I’d finally agreed.

Steven had been getting worse—wandering outside at night, forgetting my name some mornings, once even failing to recognize Clare herself. Our small town doctor in Milbrook had done what he could, but he kept saying, “You need a specialist in the city, Kathy. This is beyond me.”

The drive to Iowa City took about ninety minutes. Steven sat in the passenger seat, docile and quiet, watching the endless cornfields roll past like he was seeing them for the very first time. Clare drove, too cheerful, humming along with country songs on the radio, filling the silence with meticulously light chatter about work, traffic on I-80, and a new coffee place downtown.

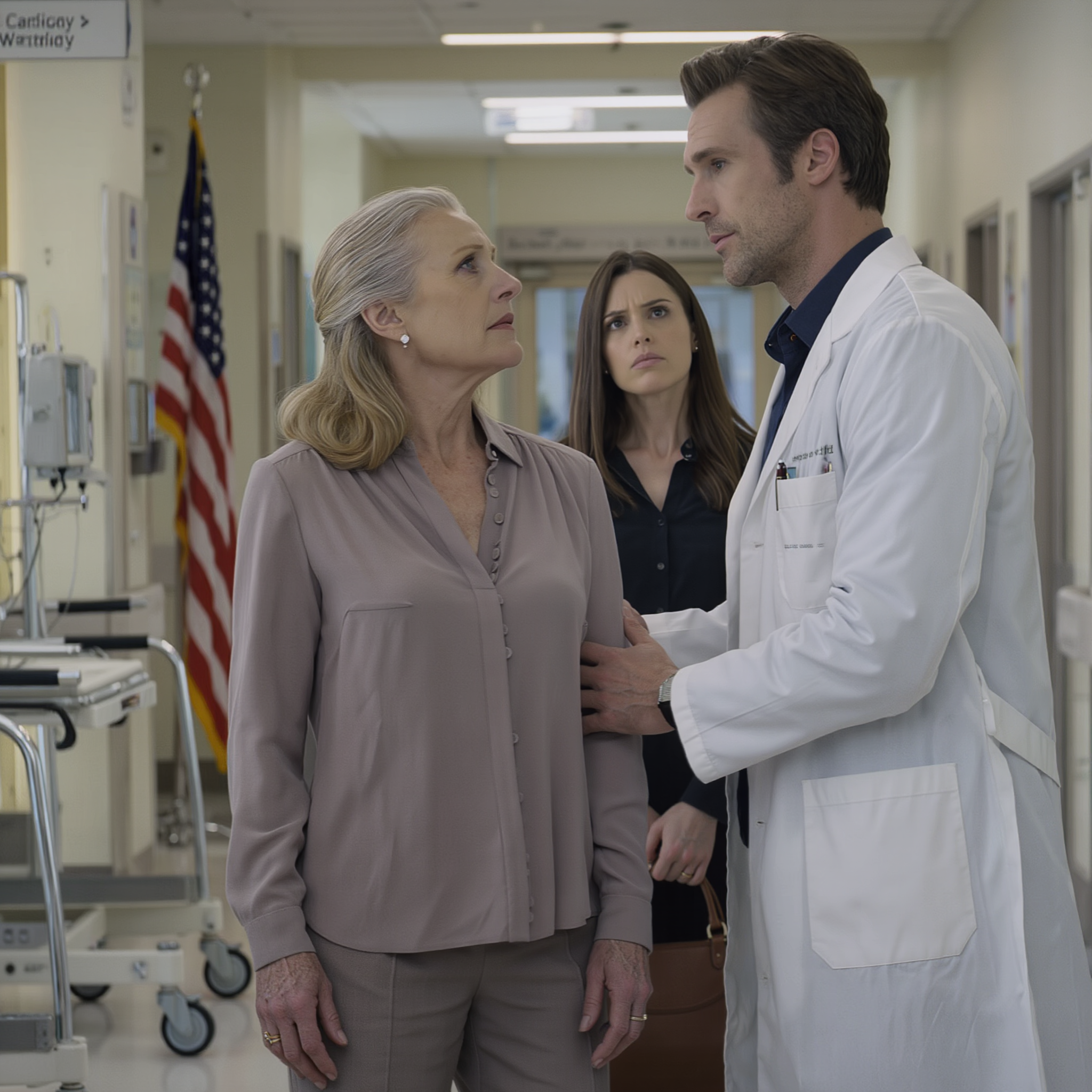

Doctor Hartley’s office was on the fourth floor. All sterile whites, muted blues, and calming nature prints. The kind of institutional calm meant to soothe people who were anything but calm.

The doctor himself was younger than I expected, maybe mid-forties, with wire-rimmed glasses and nervous hands that shuffled papers too much.

He conducted the examination with Clare and me present. Memory tests. Physical coordination checks. Questions that Steven answered with increasing confusion.

“Mr. Cuban, can you tell me what year it is?” Dr. Hartley asked gently.

Steven squinted, his forehead wrinkling as if he were trying to read something far away.

“Nineteen eighty-seven,” he said finally.

“And who is the president?” the doctor continued.

“Reagan, I believe. Unless… Ford?” Steven looked uncertain.

My throat tightened. It was 2024. He was nearly forty years adrift.

Dr. Hartley’s pen scratched across the paper with urgent speed. I noticed his hands trembling slightly. When he looked up, his eyes met mine with an intensity that startled me.

“Mrs. Cuban,” he said carefully. “I’d like to run some additional tests. Cognitive assessments, brain imaging. This level of memory loss is progressing faster than typical age-related decline.”

He paused, glancing at Clare, then back to me.

“I’d also like to check Mr. Cuban’s medication history. Sometimes certain drugs can accelerate cognitive symptoms.”

“Medication history?” Clare laughed lightly, shifting in her chair.

“Dad barely takes anything. Just his blood pressure pills.”

“And who manages his medications?” Dr. Hartley asked. He was looking at me, not her.

“Clare does,” I said. “She organizes his pill case every week when she visits. She’s been so helpful.”

Something flickered across the doctor’s face. Alarm. And something that looked very much like fear.

Before I could interpret it, Clare stood abruptly, smoothing her blouse.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I need to use the restroom. I’ll be right back.”

She smiled at both of us, but it never reached her eyes.

The moment the door closed behind her, Dr. Hartley’s entire demeanor changed.

He leaned forward, gripping his desk so hard his knuckles went white.

“Mrs. Cuban,” he whispered, his voice low and urgent, “you need to contact the authorities.”

My stomach dropped.

“The authorities? Why? What about my daughter?”

“The medication records,” he said quickly, his words tumbling over each other. “The pattern of decline, the timeline—I’ve seen this before. There are certain substances, benzodiazepines combined with other drugs, that can induce symptoms identical to dementia. They cause genuine memory loss, confusion, especially in elderly patients—but they’re reversible if caught early enough.”

The room seemed to tilt.

“What are you saying?” I whispered.

“I’m saying your husband might not have dementia at all,” Dr. Hartley replied. “He might be—”

The door opened.

Clare stood in the threshold, one hand clutching her leather purse so tightly her fingers had gone pale. Her eyes moved between Dr. Hartley and me—sharp, assessing.

“Sorry that took so long,” she said smoothly. “Is everything all right, Doctor?”

Hartley sat back so fast it was like someone had yanked invisible strings. His professional mask snapped into place so quickly I almost doubted the last thirty seconds had happened.

“Everything’s fine,” he said too quickly. “I was just explaining to your mother that we’ll need to schedule some follow-up appointments.”

But his hands were still shaking.

Clare’s gaze lingered on him a moment too long. Then she turned to me with that familiar, practiced smile.

“Ready to go, Mom?” she asked lightly. “I think Dad’s tired.”

In the car, I sat in the back seat next to Steven, who had already dozed off, snoring softly, his head tilted toward the window.

I watched the back of Clare’s head as she drove, humming along to the radio. My daughter. The little girl I’d rocked to sleep in a small nursery with yellow walls. The child whose scraped knees I had bandaged at Little League fields and church picnics. The young woman whose college dorm I had decorated with thrift-store finds and homemade quilts.

The same daughter who was now clutching her purse like it contained secrets.

Dr. Hartley’s whispered words echoed in my mind.

Contact the authorities.

Your daughter.

What had he been about to tell me? What had he seen in Steven’s records that terrified him? And why had Clare walked back into that room at that exact moment, as if she’d been listening outside the door, waiting for the right time to interrupt?

That night, after Steven was asleep, I did something I’d never done before.

I went into the guest room where Clare stayed during her visits and opened her overnight bag.

My hands trembled as I pushed aside folded clothes and a travel-sized makeup bag, as out of place in our old farmhouse as a boutique in the middle of a cornfield.

At the bottom of the bag, wrapped in a silk scarf, I found a small amber prescription bottle.

The label had been partially torn off, but I could make out part of a drug name: “…azipam.” Under that, in small print: “Not for human consumption. Veterinary use only.”

Veterinary use.

I sat on the edge of the guest bed, the bottle cold in my palm as understanding crashed over me like ice water dumped out of a metal bucket.

Clare wasn’t helping Steven.

She was drugging him.

The question that kept me awake all night wasn’t “why.” I was beginning to understand the why.

The farmhouse. The land. The inheritance. Clare’s expensive clothes and her newer, nicer car. The “investment opportunities” she’d mentioned over dinners in the city. The divorce two years ago, when her husband had left and, according to whispers at church, cleaned out their joint accounts.

She’d made some bad financial decisions. That much I knew.

The real question was: how long had this been going on? And how much of my husband had I already lost to whatever poison she’d been feeding him?

I lay in bed listening to Steven’s labored breathing in the dark. The prescription bottle was hidden in my nightstand drawer, the plastic tapping against the wood every time I opened it like a guilty heartbeat. I realized, with a sudden, crystalline clarity, that I was completely alone.

My daughter was trying to steal my husband’s mind.

And if I confronted her without proof, without a plan, she would simply vanish, taking whatever evidence existed with her.

Dr. Hartley had tried to warn me. He’d seen something in Steven’s blood work, something that made him risk his career to whisper those desperate words.

But Clare had been there. She’d heard the tone, if not the words.

She knew.

And now, lying in the darkness of the farmhouse that had sheltered four generations of Cubans through blizzards and tornado warnings and summers of drought, I understood that I wasn’t just fighting for Steven’s health or our property.

I was fighting for our lives.

Because if Clare had been poisoning Steven for four years—slowly, methodically—creating a false dementia that would justify taking control of everything we owned, then I had to ask myself a terrifying question.

What would she do if she realized I knew the truth?

The floorboards in the hallway creaked.

I held my breath, listening.

Footsteps. Soft. Deliberate. Moving past our bedroom door.

Clare, awake at two in the morning, going somewhere in my house.

I closed my eyes and pretended to sleep, clutching the prescription bottle like a talisman and silently planning my next move.

Because I had just uncovered a secret that changed everything.

And the daughter I’d raised had just become the most dangerous person in my world.

The morning after finding the prescription bottle, I woke with a clarity I hadn’t felt in years.

Fear had burned away the fog of denial, leaving behind something sharp and focused.

I was sixty-three years old, not dead. And I would not let my daughter destroy the man I’d loved for forty-two years.

But I had to be careful.

Desperately careful.

Clare came down to breakfast in her usual visiting uniform: pressed slacks, a silk blouse that probably cost more than our monthly grocery bill at Hy-Vee, and a delicate necklace that caught the early light from the kitchen window.

She kissed my cheek, squeezed my shoulder with what felt like genuine affection, and asked,

“Sleep well, Mom?”

“Like a baby,” I lied.

I watched her measure out Steven’s morning pills from the weekly organizer she’d prepared. Seven little plastic compartments, Monday through Sunday, each containing four or five tablets in various colors and shapes.

“Here you go, Dad,” she said, handing him the pills along with a glass of orange juice. “Your vitamins.”

Steven took them obediently, his eyes vacant and trusting.

My stomach twisted.

“Clare,” I said carefully, wiping crumbs off the table with a dish towel. “I was thinking… maybe we should get a second opinion. About your father’s condition.”

Her hand paused halfway to her coffee cup.

“We just saw Dr. Hartley yesterday,” she said slowly.

“I know, but he seemed rushed,” I replied. “Maybe someone who specializes more in geriatric care.”

“Mom.” Clare set down her cup and took my hand across the worn wooden table, the same table where we’d eaten countless family meals and rolled out Christmas cookie dough.

“I know this is hard,” she said gently, her voice rich with rehearsed sympathy, “but Dr. Hartley is one of the best neurologists in Iowa. We’re lucky to get in with him.”

She smiled softly.

“Sometimes we have to accept difficult realities. Dad’s not getting better. We need to focus on quality of life now. And on planning for the future.”

“What kind of planning?” I asked.

“Legal planning. Financial planning.”

She released my hand and pulled out her phone, scrolling through something.

“I’ve been researching memory care facilities,” she continued. “There’s a really nice one in Des Moines, about twenty minutes from my condo. You could visit every day and Dad would have professional care.”

“Absolutely not,” I snapped before I could stop myself.

The words came out sharper than I’d intended.

“Steven stays home. This is his home.”

For just a fraction of a second, Clare’s expression hardened, the mask slipping before she forced it back into place.

“Mom, you can’t take care of him alone,” she said in a voice that was a little too patient. “He wanders. What if he falls? What if he hurts himself? You’re not young anymore either.”

There it was.

The implication that I was too old, too fragile, too incompetent to manage my own life.

“I’m managing just fine,” I said firmly.

“Are you?” Clare stood, pushing back her chair.

“Because yesterday, you seemed confused about his medications. You didn’t even know what he was taking.”

She picked up her purse—that same leather bag she’d been clutching so tightly in Dr. Hartley’s office.

“I’m trying to help you both,” she went on. “But if you’re going to fight me on every decision, maybe we need to have a more serious conversation about your capacity to care for Dad.”

The threat hung in the air between us like smoke.

“I need to get to work,” Clare said, her voice lighter now, as if we hadn’t just been arguing over my competence.

“But think about what I said, okay? I’ll be back Friday to refill Dad’s pills and we can talk more then.”

After she left, I sat at the kitchen table for a long time, listening to the old farmhouse creak and settle around me, listening to the hum of the refrigerator and the faint sound of a tractor on the county road.

In the living room, Steven hummed tunelessly as he stared at a daytime TV program he wouldn’t remember five minutes from now.

“Your capacity to care for Dad.”

She was already building the narrative.

The elderly mother—confused, overwhelmed, unable to recognize when her husband needed professional care. It would be easy for Clare to paint me as an obstacle, to convince doctors and lawyers that Steven needed a guardian.

Namely her.

Once she had legal control, once Steven was locked away in some facility near West Des Moines, what would happen to the farm?

To me?

I pulled out the prescription bottle I’d hidden in my apron pocket. The torn label still showed that partial word: “…azipam.”

I needed to know exactly what it was.

The library in our small town of Milbrook had a couple of ancient desktop computers with internet access, stuck in a corner near a bulletin board covered in flyers for 4-H clubs, church suppers, and the county fair.

I’d never been comfortable with technology. Clare had always handled anything that required a computer. But desperation makes for a quick learner.

The young librarian, a sweet girl named Emma who had graduated from Milbrook High two years ago, helped me log on.

“Mrs. Cuban, are you feeling okay?” she asked, noticing how pale my hands looked against the keyboard.

“I’m fine, dear,” I said. “Just trying to research something for a friend.”

Within twenty minutes, we’d identified the drug.

Dazipam. Veterinary-grade. A powerful sedative used for anxious animals—big ones, mostly. Horses. Large dogs.

In humans, particularly elderly humans, it caused drowsiness, confusion, memory problems. And with long-term use, it could create symptoms indistinguishable from dementia.

“That’s terrible,” Emma murmured, reading over my shoulder. “Who would give this to a person?”

“Someone very cruel,” I whispered.

I printed the articles—Emma showed me how—and tucked them into my purse.

Evidence.

But would it be enough?

That afternoon, I called Dr. Hartley’s office.

The receptionist was polite but firm.

“Doctor Hartley can’t speak to you without the patient present,” she explained. “And his next available appointment isn’t for six weeks.”

“It’s urgent,” I insisted. “It’s about my husband’s medication.”

“If it’s a medical emergency, you should go to the ER, ma’am. Otherwise, we can schedule that appointment for January.”

I hung up, frustrated.

Dr. Hartley had tried to warn me, but now he was unreachable behind professional protocols and a wall of overworked staff.

Next, I tried calling the police.

The officer who answered listened patiently as I explained about the veterinary medication, about my daughter’s suspicious behavior, about Steven’s sudden decline.

“Ma’am,” he said finally, his voice gentle in that way officers sometimes use with elderly people, “have you actually seen your daughter give your husband this medication?”

“No,” I admitted. “But I found the bottle in her bag.”

“So you searched her belongings without permission?” he asked carefully.

“I had reason to be concerned,” I snapped.

“Mrs. Cuban,” he said, “it sounds like you’re dealing with a very stressful situation. Caring for a spouse with dementia is incredibly difficult. But what you’re describing—well, it’s a serious accusation against your own daughter. Do you have any proof she actually administered this drug? The bottle in her possession could be explained in a lot of ways. She could say she found it, or that she’s holding it for a friend with a farm. Without witnesses or documentation…”

He paused.

“Ma’am, I’m going to be honest,” he added. “This sounds like family stress. Maybe some confusion on your part. Why don’t you talk to your own doctor, or maybe a counselor who specializes in caregiver support?”

They thought I was the one losing my mind.

I felt the walls closing in like the sky before a summer storm.

Clare had been so methodical. So careful.

She organized Steven’s pills privately. She took care of everything. She presented herself to everyone as the devoted daughter managing her parents’ decline.

If I accused her publicly without ironclad proof, I would look like a paranoid old woman, possibly suffering from the same dementia I claimed Steven didn’t have.

That evening, Steven had one of his clearer moments.

They came rarely now—brief windows when the fog lifted and I caught glimpses of the man I’d married.

“Margaret,” he said suddenly, looking at me over his dinner plate.

His eyes were focused. Sharp.

“Something’s wrong. I can feel it.”

My throat tightened.

“What do you mean, honey?” I asked.

“I don’t remember things,” he said slowly. “Whole years are just gone.”

His hand shook as he set down his fork.

“And Clare… sometimes, when she thinks I’m not watching, she looks at me like… like she’s waiting for something.”

“Steven, I’m—”

“I’m not crazy,” he cut in, his voice suddenly urgent. “I know everyone thinks I am, but something’s happening to me. Something bad. I feel like I’m drowning and I can’t—”

He trailed off.

The clarity faded as quickly as it had come.

“What was I saying?” he murmured.

“Nothing, sweetheart,” I said softly. “Eat your dinner.”

But his moment of lucidity had given me an idea.

If Steven had periods of clarity, maybe those periods corresponded with times when he hadn’t taken the medication.

Clare came every Friday to refill his pill organizer.

It was Wednesday.

The drugs were probably starting to wear off.

I made a decision.

That night, after Steven was asleep, I carefully emptied Friday’s compartment from his pill organizer, documenting each pill with my phone camera. Emma had shown me how to take photos and save them.

I separated out the ones I recognized as legitimate prescriptions from our pharmacy in Milbrook—the blood pressure medication, the cholesterol pill. The others—three small blue tablets I didn’t recognize—I sealed in a plastic bag and hid in my sewing box.

Friday morning, I would give him only the legitimate medications.

If Steven improved even slightly, that would be my proof.

But I had barely finished when I heard the front door open.

“Mom? You still up?” Clare called.

She wasn’t supposed to be here until Friday.

I shoved the pill organizer back into the kitchen drawer and hurried to the living room, my heart hammering.

Clare stood in the entryway, still in her work clothes, her face tight with something that might have been anger or might have been fear.

“What are you doing here?” I asked, trying to keep my voice steady.

“I had a call today from Dr. Hartley’s office,” she said, setting her purse down with careful precision. “Apparently someone—maybe you—has been asking questions about veterinary medications and their effects on elderly patients.”

My blood ran cold.

“The receptionist mentioned it to Dr. Hartley,” she continued, “and he felt ethically obligated to inform me, as Dad’s primary caregiver, that there might be some confusion about his treatment plan.”

Clare’s eyes bored into mine.

“So I came to clear things up.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said.

“Don’t you?” Her voice was soft, almost sympathetic.

“Mom, I’m worried about you. First you’re resistant to Dad’s care. Then you’re making strange phone calls, researching random drugs. Are you feeling okay? Because this kind of paranoia, these false accusations—” She tilted her head. “They can be early signs of cognitive decline.”

The trap was closing.

She was preemptively discrediting me, building her case that I was incompetent.

“I’m perfectly fine,” I said stiffly.

“Are you?” she asked again. “Because from where I’m standing, you look exhausted. Stressed. Maybe even a little confused.”

She touched my arm gently.

“I think maybe you need help too, Mom. This is too much for you to handle alone.”

“Get out of my house,” I said.

The words surprised us both.

“Excuse me?” she whispered.

“You heard me,” I said, my voice suddenly steadier than I felt. “Come back Friday like you planned. Not before.”

For a long moment, we stared at each other.

Then Clare smiled—a cold, brittle smile that never reached her eyes.

“Of course, Mom,” she said quietly. “Whatever you want.”

She picked up her purse.

“But think about what I said,” she added. “I’m just trying to help both of you.”

After she left, I locked the front door and leaned against it, shaking.

She knew I was investigating.

She was escalating.

And I was running out of time.

Tomorrow, I would stop giving Steven the unknown pills. I would document everything. I would find a way to reach Dr. Hartley directly.

But tonight, I wedged a chair under our bedroom doorknob and barely slept, listening to every creak and whisper of the old farmhouse.

Because my daughter had just made her move.

And I had forty-eight hours to make mine before she came back to refill those pills and finish whatever plan she’d started four years ago.

Thursday morning, I gave Steven only his legitimate medications—the blood pressure pill and cholesterol tablet I’d verified with the pharmacy labels.

I watched him carefully throughout the day, looking for any signs of change.

By afternoon, something remarkable happened.

Steven looked at me while I was folding laundry in the living room and said,

“Margaret, why are you wearing that worried expression? You’ve had it for days now.”

Not just awareness.

Concern.

“I’m fine, honey,” I said, my voice trembling. “How are you feeling?”

“Tired,” he admitted. “Foggy, but less than usual, I think.”

He frowned, rubbing his temples.

“My head feels clearer. Is that strange?” he asked.

It wasn’t strange.

It was proof.

By evening, Steven was more alert than I’d seen him in months.

He remembered what we’d had for lunch. He asked about our grandson’s basketball season at Milbrook High, something he hadn’t mentioned since last year.

The fog was lifting.

But I knew Clare would be here tomorrow. And the moment she refilled his pill organizer, this clarity would vanish again.

I needed help.

Real help.

Someone who would believe me.

That night, I did something that terrified me.

I called our son.

James lived in Chicago, worked in finance, and visited maybe twice a year. He and Clare had never been close. She’d always been jealous of the attention he got as the baby of the family, despite being only two years younger.

After his father started declining, James had essentially left everything to Clare.

“My work’s too demanding, Mom,” he’d said more than once. “Clare’s closer. She can handle things.”

“Mom?” he answered now, his voice worried. “Is everything okay? Is it Dad?”

“James,” I said, gripping the phone so tightly my knuckles hurt, “I need to tell you something. But you have to promise to hear me out completely before you react.”

“You’re scaring me,” he said.

“Good,” I replied. “You should be scared.”

I took a breath.

“Your sister has been poisoning your father.”

Silence.

Then, “What?”

I told him everything.

The bottle. The veterinary medication. Dr. Hartley’s warning. Steven’s sudden improvement after I stopped the unknown pills.

I spoke quickly, urgently, knowing how insane it all sounded.

“Mom, stop,” James said, his voice pained. “Just… stop.”

“I won’t,” I said. “You need to hear this.”

“Do you hear yourself?” he asked. “You’re accusing Clare of attempted murder.”

“I’m accusing her of inducing false dementia to gain control of our assets,” I corrected. “Based on what? A bottle you found in her bag? Pills you can’t identify?”

“I identified them,” I said. “With Emma’s help. Dazipam. Veterinary-grade. In humans, it causes—”

“Mom,” he interrupted, “Clare has been the only one taking care of you and Dad. She drives up every week—to drug him.”

“To help him,” he insisted. “While I’ve been in Chicago and you’ve been in denial about how sick Dad really is, Clare’s been handling everything. The doctor appointments, the medications, the legal stuff you won’t even think about.”

“What legal stuff?” I asked.

Another pause. This one felt heavier.

“James,” I said slowly, “what legal stuff?”

“Clare didn’t want to worry you,” he said finally, “but she’s been working with a lawyer. Getting power of attorney papers drawn up. Updating the will. Looking into what happens if both you and Dad become incapacitated.”

My hands went numb.

“She’s doing what?” I whispered.

“Smart planning, Mom,” James said. “Responsible planning. Because someone has to think about these things, and apparently it’s not going to be you.”

“Did you sign anything?” I asked. “Did she ask you to witness documents?”

“I… yes,” he said. “A few months ago, when I visited. Clare said it was standard stuff. Making sure Dad’s wishes were documented while he could still technically consent.”

“While he was drugged into incompetence, you mean,” I said.

“Mom, I love you,” James said softly, “but you need to listen to yourself. This paranoia, these wild theories… maybe you should see a doctor. The stress of caregiving, it can cause—”

I hung up.

My own son thought I was crazy.

Worse, he’d already helped Clare with legal documents.

What had he signed?

What had Steven signed while his mind was clouded with veterinary sedatives?

I sat in the dark kitchen for a long time, the ticking clock on the wall suddenly deafening.

Then I remembered Emma at the library.

Young, tech-savvy Emma, who’d helped me research the drugs.

Friday morning, I drove to town early, leaving Steven with our neighbor, Mrs. Patterson—a sharp-eyed widow in her seventies who’d lived down the gravel road for thirty years.

“Margaret, is something wrong?” she’d asked when I called.

“Yes,” I’d said. “But I need help, not questions. Can you sit with Steven for a few hours? Don’t let anyone in the house except me. Not even Clare. Especially not Clare.”

Mrs. Patterson had agreed without further comment.

I could have kissed her.

At the library, Emma was shelving books near the section of old Western paperbacks.

Her face brightened when she saw me, then fell when she noticed my expression.

“Mrs. Cuban, what’s wrong?” she asked.

“Emma, I need help,” I said. “And I need you not to ask too many questions.”

What Emma had that I didn’t was knowledge of computers and, more importantly, social media.

Within an hour, she’d found Clare’s Facebook page, her Instagram, her LinkedIn profile—all perfectly curated: brunches in downtown Des Moines, charity galas, yoga selfies, and photos from expensive-looking restaurants in Chicago and Minneapolis.

“Your daughter lives quite well,” Emma observed carefully, scrolling through photos of Clare in designer dresses, standing in front of what appeared to be a newly renovated condo with a skyline view.

“She does,” I said. “On what salary, I’m not sure.”

Emma clicked on a tagged photo from six months ago.

Clare stood at some kind of charity gala, her arm around a distinguished-looking man in his fifties.

The caption read: “With my favorite attorney. Thanks for everything, Richard.”

“Can you find out who that man is?” I asked.

Emma’s fingers flew across the keyboard.

“Richard Thornton,” she said. “Estate planning attorney in Des Moines. Specializes in elder law and probate.”

“Can you print his office information?” I asked.

“Already doing it,” she replied.

I liked this girl very much.

Armed with the attorney’s address, I drove straight to Des Moines.

I’d never been bold enough to do something like this before—just show up at a lawyer’s office without an appointment. Des Moines still felt like “the city” to me, all busy streets and glass office buildings and people who never made eye contact.

But desperation had burned away my Midwestern politeness.

Richard Thornton’s office was on the twelfth floor of a downtown building with underground parking and a sleek glass lobby. His receptionist tried to turn me away.

“Mr. Thornton is with clients all afternoon,” she said with a corporate smile.

“Tell him Kathy Cuban is here,” I said, planting my purse on the counter like I belonged there. “Tell him it’s about Clare Cuban and the documents involving Steven Cuban’s estate. Tell him that if he doesn’t see me in the next five minutes, I’m going directly to the State Bar Association with questions about his ethics.”

I had no idea if that was even a real threat.

But it worked.

Three minutes later, I was in Richard Thornton’s office.

He was the man from Clare’s photo. Perfectly groomed, professionally pleasant, but his eyes were wary.

“Mrs. Cuban,” he began, gesturing for me to sit. “I’m not sure what Clare has told you—”

“Nothing,” I cut in. “She’s told me nothing. Which is why I’m here.”

I sat down without being invited.

“What documents have you prepared involving my husband and our property?” I asked.

“I’m afraid that’s confidential,” he said. “Attorney-client privilege.”

“Mr. Thornton,” I said, keeping my voice steady, “my husband has been systematically drugged with veterinary sedatives for at least four years, creating artificial dementia symptoms. During that time, my daughter has apparently had him sign legal documents. I’m guessing—and correct me if I’m wrong—that those documents give her significant control over our assets.”

The color drained from Thornton’s face.

“That’s… that’s a serious accusation,” he said weakly.

“It’s a statement of fact,” I replied. “And if you knowingly participated in obtaining legal consent from an incapacitated person, you’re complicit.”

“I had no idea,” he said quickly. “I mean, Clare presented medical records, cognitive assessments—”

“From what doctor?” I demanded.

“Dr. Michael Hartley,” he said. “The reports clearly showed advancing dementia.”

He shuffled through some papers and stopped, realizing what he was confirming.

“May I see those reports?” I asked.

“I can’t just show you client documents,” he protested.

“I’m not a client,” I said. “But my husband is. Or was.”

I leaned forward.

“Mr. Thornton,” I said quietly, “I’m sixty-three years old. I’ve never threatened anyone in my life. But right now, you have a choice. You can help me understand what my daughter has done, or you can wait for the police to arrive and ask those questions themselves. Because I’m leaving here and going directly to the county sheriff with everything I know.”

“The police won’t believe—” he began.

“Maybe not,” I said. “But they’ll investigate. And when they do, what will they find? A lawyer who helped a woman steal from her elderly, incapacitated parents? Or a lawyer who, when he realized something was wrong, did the right thing?”

Richard Thornton stared at me for a long moment.

Then he pressed the intercom button.

“Stephanie,” he said to his assistant, “cancel my next appointment and bring me the Cuban family files.”

What I learned in the next thirty minutes destroyed whatever remained of my heart.

Clare had been planning this for five years.

The documents Thornton showed me painted a picture of methodical, calculated theft disguised as concerned caregiving.

Power of attorney papers signed eighteen months ago, when Steven was heavily medicated. A new will replacing the one Steven and I had made together, leaving everything to Clare with only a small trust for James.

Quitclaim deeds transferring portions of the farm property into Clare’s name. Signed by Steven, notarized, completely legal—as long as no one questioned his mental capacity at the time.

“She told me you were in denial about your husband’s condition,” Thornton said quietly. “That you were refusing to accept reality and making care decisions difficult. She positioned herself as the responsible child trying to protect her parents’ interests.”

“While stealing everything we own,” I finished for him.

“Mrs. Cuban,” he said, his voice shaking, “I swear I had no idea.”

“You had Dr. Hartley’s reports,” I said. “What did they say?”

“Progressive dementia,” he replied. “Cognitive decline. Inability to make complex decisions.” He frowned, holding one of the reports up to the light. “Wait. What? These reports… the signature.” He squinted. “This isn’t Dr. Hartley’s signature. I’ve seen his signature on other documents. This is different.”

The reports were forgeries.

Clare had created false medical records to justify Steven’s incapacity.

“She’s a fraud examiner,” I said slowly. “Her job is detecting financial crimes. She knows exactly how to fabricate documents that look legitimate.”

Thornton’s hands were shaking now.

“If this is true,” he whispered, “if I’ve been party to elder abuse and fraud—”

“You’ve been played,” I said flatly. “Just like everyone else.”

I gathered the papers into a neat stack.

“I need copies of all of this,” I said.

“I can’t just give you—” he started.

“You can,” I said. “Because you know what she’s done. And you know that your choice right now is to help fix it, or go down with her.”

Ten minutes later, I walked out of Richard Thornton’s office with a folder full of damning evidence and his promise to cooperate with any investigation.

I was halfway back to Milbrook, my mind reeling, when my phone rang.

“Mrs. Patterson,” I answered, seeing her name flash on the screen. “Is everything okay?”

Her voice was tight with fear.

“Margaret, you need to come home now,” she said.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, my heart racing.

“Clare is here,” Mrs. Patterson said. “She arrived twenty minutes ago with a police officer and someone from Adult Protective Services. She’s saying you’ve been neglecting Steven, that you’re mentally unstable, that you left him alone in an unsafe situation. They’re talking about taking him into emergency custody.”

The folder of evidence sat on the passenger seat beside me.

Clare didn’t know I had it.

She didn’t know Thornton had flipped.

She thought she was still one step ahead.

But she’d made a mistake.

She’d pushed too hard. Too fast.

“Tell them I’m five minutes away,” I said into the phone. “Tell them not to move Steven anywhere until I arrive.”

“What are you going to do?” Mrs. Patterson asked.

“Something I should have done four years ago,” I said. “I’m going to fight.”

I pressed the accelerator, gravel pinging off the underside of the truck as the old farmhouse came into view over the hill.

My daughter was waiting inside with her police escort and her lies.

But I had the truth now. Documentation. Proof.

And sixty-three years of patience that had finally, completely run out.

I pulled into our driveway to find three vehicles parked half-haphazardly across the gravel: Clare’s shiny BMW, a county sheriff’s cruiser, and a white sedan with state government plates.

My hands gripped the steering wheel so tightly my knuckles ached.

Through the living room window, I could see figures moving. Clare’s distinctive silhouette. The outline of a uniformed officer. A woman in a business suit holding a clipboard.

Mrs. Patterson appeared on the front porch, her face grave.

“Margaret, they’re saying—” she began.

“I know what they’re saying,” I cut in.

I grabbed the folder from the passenger seat.

“Is Harold here?” I asked.

“Just arrived,” she said. “He’s inside with Steven.”

Harold Kemper had farmed the adjacent property for forty years. He was also a retired county supervisor who’d served on the zoning board and knew exactly how official procedures were supposed to work.

More importantly, he’d brought his camera, just as I’d asked in a hurried text.

I walked into my own home feeling like an intruder.

Clare stood in the center of the living room, her face arranged in an expression of pained concern that I’d seen her use before on coworkers and church ladies.

Next to her stood Deputy Warren, a young man I recognized from church, and a serious-looking woman in her forties wearing a badge that identified her as Linda Morrison, Adult Protective Services.

“Mom,” Clare said, rushing toward me. “Where have you been? We’ve been worried sick.”

I stepped back.

She froze, hurt flashing across her face.

Perfect performance.

“I had errands in Des Moines,” I said.

“You left Dad alone,” she said, eyes widening.

“I left him with Mrs. Patterson,” I replied. “As you well know, since she’s been here the entire time.”

I turned to the social worker.

“Ms. Morrison, I assume?” I asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “We received a report of possible elder neglect and self-neglect. Your daughter indicated that your husband has advanced dementia and was left unattended this morning.”

“He was attended by a trusted neighbor,” I said. “Who has known us for thirty years.”

“A neighbor is not qualified medical care,” Clare interjected quickly.

“Neither is unnecessary institutionalization,” I shot back.

I turned to Deputy Warren.

“Did my daughter claim there was an emergency?” I asked. “A specific danger to my husband?”

Warren shifted uncomfortably.

“Ma’am, we’re just following protocol on a wellness check,” he said.

“Show me the report,” I said to Morrison. “I have a right to see what allegations have been made.”

She hesitated, then handed me her tablet.

I read quickly, my blood pressure rising with each line.

According to Clare’s report, filed that very morning, I was suffering from increasing paranoia and delusional thinking. I had accused Clare of poisoning Steven. I had made concerning phone calls to police and medical offices, making “false claims.” I had abandoned Steven in a potentially dangerous situation that day.

The report painted me as an unstable elderly woman experiencing cognitive decline, unable to care for herself or her husband.

“These are lies,” I said, looking directly at Clare. “Calculated, documented lies.”

“Mom,” Clare said, her voice soft, “you’re not thinking clearly.”

“I’m thinking more clearly than I have in years,” I replied.

I opened the folder from Thornton’s office and spread the papers across our coffee table.

“Deputy Warren. Ms. Morrison. I’d like to show you something,” I said.

“These are legal documents that were signed by my husband over the past two years. Documents I knew nothing about until this morning.”

Clare’s face went white.

“Where did you get those?” she demanded.

“From the attorney who prepared them,” I replied calmly. “Richard Thornton. Who is very concerned about the circumstances under which they were signed.”

I pointed to the power of attorney documents, the property transfers, the forged medical reports with Dr. Hartley’s falsified signature.

“My husband has been systematically given veterinary-grade sedatives for approximately four years,” I said. “Creating symptoms of dementia. During that time, these documents were prepared and signed while he was incapacitated.”

I pulled out the prescription bottle I’d found in Clare’s bag.

“This is dazipam,” I said. “Veterinary use only. I found it in my daughter’s possession.”

Morrison picked up the bottle, her expression shifting.

Warren leaned in to look at the documents.

Clare laughed, a sharp, brittle sound.

“This is exactly what I was talking about,” she said. “These paranoid delusions.”

“Dr. Hartley tried to warn me,” I continued. “At Steven’s last appointment, he attempted to tell me that the medication pattern suggested drug-induced cognitive impairment. My daughter interrupted before he could finish. But I suspect if you contact Dr. Hartley directly, he’ll confirm he never signed these medical reports and that he has serious concerns about the medications Steven has been receiving.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Clare snapped.

“Is it?” a new voice said.

Harold stepped forward.

“I’ve known Steven Cuban for forty years,” he said. “And I watched him this morning. He’s more lucid than I’ve seen him in ages. Asked me about corn futures and remembered my daughter’s name—something he couldn’t do last month.”

“That’s just a good day,” Clare said quickly.

“Margaret also asked me to document Steven’s current state,” Harold went on.

He pulled out a small notebook.

“I had a fifteen-minute conversation with him,” he said. “Coherent. Rational. Oriented to time and place. That’s not advanced dementia.”

Morrison was reading the legal documents with increasing concern.

“Mrs. Cuban,” she said slowly, “these property transfers… if they were obtained under duress or while Mr. Cuban was incapacitated, they’re fraudulent.”

“Exactly,” I said. “Which is why I’m requesting a full investigation.”

“Mom, stop,” Clare pleaded. “You’re destroying our family over paranoid fantasies. I’ve dedicated the last four years to caring for you and Dad.”

“You’ve dedicated the last four years to stealing from us,” I said.

I pulled out my phone.

“Emma at the library taught me how to use the voice recorder,” I said. “I’ve documented everything. The pills you’ve been giving Steven. The timing of his decline. The improvements when the medication is stopped. I have statements from the attorney. I have the veterinary medication with your fingerprints on it.”

That last part was a bluff. I had no idea if fingerprints could be recovered.

But Clare didn’t know that.

“This is insane,” she said, turning frantically to Morrison and Warren. “Can’t you see? She’s having a breakdown. She needs help.”

“What I need,” I said quietly, “is for you to leave my house.”

The room fell silent.

Clare stared at me, and for a moment, the mask slipped entirely.

What I saw beneath wasn’t grief or concern or even anger.

It was cold calculation, rapidly assessing whether her plan could still be salvaged.

“Ms. Cuban,” Morrison said carefully, “I think we need to take a step back here. These are serious allegations on both sides.”

“I want my daughter arrested for elder abuse, fraud, and attempted theft,” I said.

“Mom,” Clare whispered. “How can you say that? I’m your daughter. I’ve been trying to help.”

“By drugging my husband into incompetence,” I replied. “By forging medical documents. By stealing our property. You’re right about one thing, Clare. You are my daughter. Which makes this betrayal hurt more than I can possibly express.”

“I didn’t—I never—” she stammered, turning again to the authorities.

“Are you going to let her make these insane accusations?” she demanded. “Where’s her evidence? One bottle of medication that could have come from anywhere? Some papers she claims were signed under duress? This is harassment.”

Warren looked uncomfortable.

“Mrs. Cuban… Margaret,” he said, “I understand you’re upset. But we can’t make an arrest without more substantial evidence. We’d need to verify the medication, contact Dr. Hartley, review the documents with the county attorney—”

“Then do that,” I said. “Start investigating. Now.”

“It doesn’t work that fast,” he said apologetically.

“Then in the meantime,” I said, “I want her removed from my property.”

“Mom, please,” Clare said.

“You’re not welcome here anymore,” I said. “You don’t have keys. You don’t have permission. And if you set foot on this land again without my explicit consent, I’ll have you arrested for trespassing.”

Clare’s tears stopped instantly.

“Fine,” she said. “You want to do this? You want to destroy everything?”

She grabbed her purse.

“I’ll see you in court, Mother,” she spat. “Because if you think you’re competent to make decisions, we’ll let a judge determine that. And when they see how confused and paranoid you’ve become, when they see how you’ve neglected Dad, they’ll appoint a guardian. And it won’t be you.”

She stormed out.

Her BMW’s engine roared to life, gravel spraying as she accelerated down the driveway toward the county road.

Morrison closed her tablet.

“Mrs. Cuban,” she said, “I’m going to need to conduct a full assessment of your home, your husband’s condition, and your ability to provide adequate care.”

“Of course,” I said.

“Assess anything you’d like. You’ll find Steven is properly cared for. This house is safe. And I’m completely competent.”

“I’ll also need to file a report about these allegations against your daughter,” she added. “This will trigger an investigation.”

“Good,” I said. “That’s exactly what I want.”

After Morrison and Warren left, promising to return the next day for a formal assessment, I collapsed onto the sofa.

My hands were shaking.

Adrenaline drained from my body, leaving me lightheaded.

“You did good, Margaret,” Harold said, squeezing my shoulder. “Real good. That took courage.”

“It took desperation,” I replied.

Mrs. Patterson brought tea in mismatched mugs.

“What happens now?” she asked.

“Now the system moves at its glacial pace,” Harold said, “and Clare lawyers up.”

I stared at the folder of documents.

“She won’t go down quietly,” I said.

I was right.

That evening, James called.

“Mom,” he said, his voice tight, “what the hell did you do? Clare just called me crying, saying you’ve gone crazy, that you threw her out and accused her of poisoning Dad.”

“I didn’t go crazy, James,” I said. “I woke up. There’s a difference.”

“She says you have some insane conspiracy theory,” he insisted.

“It’s not a theory,” I said. “It’s documented fact. I have the evidence. The question is whether you’re going to believe your mother or your sister. There is no middle ground.”

“I told him everything,” I said.

I sat there at the kitchen table with the phone pressed to my ear and laid it all out for my son. The bottle. The veterinary medication. Dr. Hartley’s warning. Steven’s sudden improvement after I stopped the unknown pills. The legal documents. The forged reports.

I spoke quickly, urgently, words coming out in a tight stream because I knew how insane it all sounded, even to my own ears.

“Mom, stop,” James finally said. His voice was pained. “Just stop.”

“I won’t,” I said quietly. “You need to hear this.”

“Do you hear yourself?” he asked. “You’re accusing Clare of attempted murder.”

“I’m accusing her of inducing false dementia to gain control of our assets,” I replied.

“Based on what?” he demanded. “A bottle you found in her bag? Pills you can’t identify?”

“I did identify them,” I said. “With Emma’s help. Dazipam. Veterinary-grade. In humans it causes confusion, memory loss, sedation. In the elderly, it can look exactly like dementia.”

“Mom,” he sighed, “Clare has been the only one taking care of you and Dad. She drives up every week—”

“To drug him,” I cut in.

“To help him,” James insisted. “While I’ve been in Chicago and you’ve been in denial about how sick Dad really is. Clare’s been handling everything. The appointments, the meds, the legal stuff you won’t even talk about.”

“What legal stuff?” I asked.

There was a pause.

“James,” I said slowly, “what legal stuff?”

“Clare didn’t want to worry you,” he said at last, “but she’s been working with a lawyer. Getting power-of-attorney papers drawn up. Updating the will. Looking into what happens if both you and Dad become incapacitated.”

My fingers went numb around the phone.

“She’s doing what?” I whispered.

“Smart planning, Mom,” he said. “Responsible planning. Because someone has to think about these things and apparently it’s not going to be you.”

“Did you sign anything?” I asked. “Did she ask you to witness documents?”

Another pause.

“I… yes,” he admitted. “A few months ago when I visited. Clare said it was standard stuff. Making sure Dad’s wishes were documented while he could still technically consent.”

“While he was drugged into incompetence, you mean,” I said.

“Mom, I love you,” James said, frustration thick in his voice, “but you need to listen to yourself. This paranoia, these wild theories… maybe you should see a doctor. The stress of caregiving, it can—”

I hung up.

For a moment I just sat there, staring at the phone in my hand.

My own son thought I was crazy.

Worse, he had already helped Clare with legal documents.

What had he signed? What had Steven signed while his mind was soaked in sedatives meant for animals?

The house was quiet around me, the ticking clock on the kitchen wall suddenly loud as a hammer.

I picked up the folder from Thornton’s office and ran my hand over it.

Then I thought of Emma.

Young, stubborn, sharp-eyed Emma at the library, who had treated my questions like a mystery to be solved instead of the ramblings of an old woman.

If no one else believed me, maybe she still would.

Friday morning, I loaded Steven’s breakfast tray, set out his medications—the legitimate ones—and drove to town at first light.

Mrs. Patterson met me at the door before I could knock.

“Go,” she said. “I’ve got him. And I’ll keep the doors locked. If Clare shows up, I’ll stall her.”

“Don’t let her in,” I said.

“I won’t,” she replied. “I’ve lived in Iowa seventy-two years, Margaret. I know how to stand my ground.”

At the library, Emma was straightening a paperback display.

“Back again,” she said, then stopped when she saw my face. “What happened?”

“We found my daughter’s lawyer,” I said. “He showed me the paperwork. Power of attorney, a new will, deeds to the farm.” I swallowed. “She forged medical reports from Dr. Hartley.”

Emma’s eyes widened.

“What do you need me to do?” she asked.

“Nothing more,” I said gently. “You’ve already helped more than you know. I just wanted to tell someone I’m not crazy.”

“You’re not crazy,” she said. “You’re mad. There’s a difference.” Then, after a beat, “So what’s next?”

“Next,” I said, “I go to the sheriff. For real this time. With proof.”

Except the sheriff wasn’t the next step.

The next step was the emergency room.

That night, after the confrontation in my living room, after the threats and the promises and the official phrases from APS and the deputy, I lay awake and replayed Thornton’s words in my head.

If this is true, this is elder abuse.

Elder abuse.

They used that term on the news sometimes, with stock footage of nursing homes and grim voice-overs. It had always seemed like something that happened in other places, to other people.

Not here.

Not to us.

Emma had shown me how to save photos and files to my phone. I scrolled through them now: the pill compartments, the blue tablets, the forged signatures.

It wasn’t enough.

I needed something undeniable.

Blood work.

I drove Steven to the emergency room in Cedar Rapids at six o’clock Saturday morning, before Clare could learn what I was planning, before she could make any more calls or move any more pieces on the board.

The ER waiting room smelled like antiseptic and burned coffee. A TV in the corner muttered cable news at a low volume. A young father sat with a toddler who was clutching a stuffed dinosaur and whispering through tears.

We checked in at the desk. The nurse looked at Steven, at me, at the shaky way Steven held his insurance card.

“What brings you in today, ma’am?” she asked.

“I think my husband has been given medication he’s not supposed to have,” I said. “For a long time.”

We were taken back to an exam room. Steven sat on the edge of the bed in a pale blue hospital gown, his feet dangling above the tile floor.

The ER doctor, a tired-looking woman in her thirties with dark hair pulled into a bun, introduced herself as Dr. Santos.

“Tell me what’s going on,” she said.

I told her.

Everything.

I laid the pill bottle and Thornton’s documents on the tray table between us. I explained the timeline, Clare’s role, the forged reports, the sudden improvement when the unknown pills were removed.

The more I spoke, the more the doctor’s expression changed—from guarded politeness to alert focus.

“You’re saying you believe your husband has been given veterinary sedatives without his knowledge,” she said, clarifying.

“I don’t believe it,” I replied. “I know it. I just need someone to prove it.”

Dr. Santos picked up the bottle, studied the label, then glanced at Steven.

“Can you tell me what day it is, Mr. Cuban?” she asked.

“Saturday,” he said, after a pause. “Or maybe Sunday. I’m not sure.”

“Do you know where you are?”

“Hospital,” he said. “Cedar Rapids. My wife drove me.”

She nodded.

“We’ll run a full toxicology screen,” she said. “Everything in his system.”

The blood work took four hours.

I paced the hallway. I watched nurses move briskly from room to room. I listened to the faint sounds of monitors beeping and overhead announcements about cardiology consults.

When Dr. Santos finally came back, her face was grim.

“Mrs. Cuban,” she said, “your husband has significant levels of dazipam in his system, along with traces of another benzodiazepine—alprazolam. The concentrations suggest chronic, regular dosing over an extended period of time.”

“Chronic,” I repeated.

“Yes,” she said. “These drugs, especially in elderly patients, can cause severe cognitive impairment, memory loss, confusion—all symptoms that mimic dementia.”

“Can it be reversed?” I asked.

She hesitated.

“If we stop the medications and allow them to clear his system, yes,” she said. “His cognitive function should improve significantly. There may be some permanent effects, depending on how long he’s been drugged. But it is very likely that many of his symptoms are medication-induced.”

Her expression hardened.

“Mrs. Cuban,” she added, “I’m mandated to report this. What you’re describing is serious elder abuse.”

“Good,” I said. “Report it. I want everything documented.”

Dr. Santos filed her report with Adult Protective Services and the county sheriff’s office. She also wrote a detailed medical opinion stating that Steven’s symptoms were consistent with drug-induced cognitive impairment, not organic dementia.

Armed with this new evidence, I drove straight to the office of Catherine Brennan, the attorney Harold had recommended.

Her office was in an old brick building near the river, the kind of place that had once been a hardware store and now housed law firms and accountants.

Catherine was sixty-eight, with a no-nonsense gray bob and sharp blue eyes. A former prosecutor who had specialized in elder abuse cases before going into private practice.

“Your timing is fortunate,” she said after I’d finished explaining. She spread my documents across her conference table: Thorntons files, Dr. Santos’s report, the photos, my notes.

“I received a call yesterday from the county attorney’s office,” she went on. “They’re opening an investigation into your daughter based on the APS report and Dr. Hartley’s statement.”

“Dr. Hartley gave a statement?” I asked.

“As soon as he learned about your visit to Richard Thornton’s office,” Catherine said, “he contacted authorities. Apparently he’s been concerned about your husband’s medications for months but couldn’t act without concrete evidence of wrongdoing.”

She tapped the toxicology report.

“This is that evidence,” she said. “Combined with the forged medical documents and the property transfers, you have a very strong case.”

“Clare says she’s going to have me declared incompetent,” I said.

Catherine gave a short, humorless laugh.

“She’s welcome to try,” she said. “But her credibility is badly damaged now. And you have medical professionals backing your version of events.”

She slid a legal pad toward me.

“Now we go on offense,” she said. “I’m filing for emergency injunctions to freeze all property transfers, void the fraudulent power of attorney, and restore your husband’s rights. I’m also requesting the court appoint an independent guardian ad litem to investigate.”

She pulled out a calendar.

“There’s a hearing scheduled for Tuesday morning,” she said. “The county attorney will present their evidence. I’ll present ours. And Clare will have to defend herself.”

“Will she be arrested?” I asked.

“Possibly,” Catherine said. “If the judge believes there’s sufficient evidence of fraud and elder abuse, they could issue a warrant.”

Her expression softened.

“But Margaret,” she added, “you need to prepare yourself. This is going to get ugly. Your daughter will fight back with everything she has. She’ll try to discredit you. She’ll bring up every moment you’ve ever forgotten a date or misplaced keys. She’ll suggest you’re confused, vindictive, unstable. She’ll use your age against you.”

I nodded.

“Let her try,” I said. “I have the truth.”

“Truth and perception aren’t always the same thing in court,” Catherine replied. “But we’ll do everything we can to make them match.”

Tuesday morning arrived cold and gray, one of those Iowa days when the sky felt low and heavy.

I dressed carefully in my best church dress, the navy one with the modest neckline and clean lines. I pinned my hair back, put on minimal makeup, and slipped my old wedding ring back on my finger for courage.

Harold and Mrs. Patterson came with me, one on each side as we walked up the courthouse steps.

Steven stayed home with a private nurse Catherine had arranged, his blood finally clearing of the drugs that had stolen four years of his life.

The courtroom was smaller than I expected, its wood-paneled walls and worn benches smelling faintly of dust and floor polish.

Clare sat at the defendant’s table with two attorneys in tailored suits. She wore a simple gray dress, minimal makeup, her hair pulled back in a low bun. She looked younger and smaller than I remembered.

She didn’t look at me.

Judge Patricia Winters entered, a silver-haired woman in her sixties who carried herself like someone who had been listening to lies and truth for decades and knew the difference more often than not.

She reviewed the files in front of her with slow, deliberate care before speaking.

“This is a preliminary hearing regarding allegations of elder abuse, fraud, and financial exploitation,” she began. “Ms. Cuban, you’re not being criminally charged at this time, but these proceedings will determine whether criminal charges are warranted. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Clare said softly.

The county attorney, a sharp-eyed man named David Morton, presented first.

He laid out the story piece by piece: the toxicology report showing benzodiazepines in Steven’s system, Dr. Hartley’s concerns, Dr. Santos’s findings, the forged medical records, the property transfers, the veterinary medication.

“Your Honor,” he concluded, “the evidence suggests a systematic, premeditated scheme to incapacitate Steven Cuban and steal his assets. The defendant positioned herself as the primary caregiver, isolated the victim from other family members and medical professionals, and used her access to administer drugs that created artificial dementia symptoms. She then exploited those symptoms to obtain legal documents giving her control over substantial property and financial assets.”

Clare’s attorney rose.

“Your Honor,” he said, “my client categorically denies these allegations. What the county attorney characterizes as evidence is actually a tragic misunderstanding driven by Mrs. Kathy Cuban’s own cognitive decline.”

“Objection,” Catherine said sharply. “There is no evidence of cognitive decline in my client.”

“Isn’t there?” Clare’s attorney said smoothly.

He produced a folder.

“My client has documented numerous instances over the past two years of concerning behavior from Mrs. Cuban,” he said. “Memory lapses. Confusion about dates and events. Increasing paranoia.”

“Any so-called documentation created by the defendant is inherently suspect,” Catherine cut in, “given her demonstrated willingness to forge medical records.”

Judge Winters raised a hand.

“I will review all submitted documentation,” she said. “Continue, Mr. Morton.”

The county attorney called Dr. Santos.

She explained the toxicology findings in plain language. The drugs. The dosages. The likely effects in a seventy-four-year-old man.

“In your medical opinion,” Morton asked, “are Mr. Cuban’s symptoms more consistent with dementia or with drug-induced cognitive impairment?”

“Drug-induced,” she said firmly. “In my opinion, the medications are the primary cause of his cognitive issues.”

Then Catherine called Dr. Hartley.

He looked nervous but determined.

“Your Honor,” he said, “I attempted to warn Mrs. Cuban during our last appointment that I suspected drug-induced cognitive impairment. The pattern of symptoms, the rapid progression, the medication history—it all suggested something other than natural dementia. When I reviewed Mr. Cuban’s blood work, I found irregularities that weren’t consistent with his prescribed medications.”

“Why didn’t you report this sooner?” the judge asked.

“I tried,” he said, glancing briefly at Clare. “I contacted Ms. Clare Cuban, listed as the primary caregiver, to discuss my concerns. She became defensive and threatened to report me for malpractice if I suggested her father was anything other than genuinely ill. I should have gone to authorities then. I didn’t. And I deeply regret that decision.”

Clare’s attorney cross-examined him aggressively.

“Dr. Hartley,” he said, “isn’t it true you saw Mr. Cuban exactly once? How can you make a definitive diagnosis based on a single appointment?”

“I reviewed extensive medical records,” Hartley said.

“Records that allegedly were forged by my client,” the attorney shot back. “Which would mean you’re basing your opinion on fraudulent information. How do you know what’s real and what isn’t?”

“The toxicology report is real,” Hartley said. “The drugs in Mr. Cuban’s system are real.”

“But you can’t prove who administered them, can you?” the attorney pressed. “Mrs. Cuban has documented—”

“Mrs. Cuban, whom you met once,” the attorney continued, “and who has her own obvious bias in this situation.”

When the judge called a recess, my hands were shaking.

In the hallway outside the courtroom, Catherine pulled me aside.

“They’re good,” she said. “They’re going to argue that even if Steven was drugged, there’s no direct evidence Clare did it. That the medication bottle could have come from anywhere. That you could be the one administering the drugs and blaming Clare to cover your own actions.”

“That’s absurd,” I said.

“That’s reasonable doubt,” Catherine replied. “We need something more. Something that directly ties Clare to the drugs.”

I thought frantically.

The bottle with her fingerprints. Maybe. The timing of Steven’s decline corresponding to her increased visits. The forged reports. Still, all of it could be spun.

Then I remembered the pill organizer.

The one she filled every week.

“Catherine,” I said, “Clare prepares Steven’s pills every Friday. A seven-day organizer. It’s still on our kitchen counter with this week’s pills. Pills she prepared before I started pulling anything out. Can we test those?”

Catherine’s eyes sharpened.

“Where is it now?” she asked.

“At the house,” I said. “In the kitchen drawer.”

She grabbed her phone and called the private nurse.

“This is Catherine Brennan,” she said. “I need you to secure a medication organizer in the Cuban kitchen. Don’t touch it, don’t let anyone else touch it. The sheriff’s department will send someone to collect it as evidence.”

When court resumed, Catherine requested a brief extension to allow analysis of additional evidence. Judge Winters agreed, scheduling a continuation for the following week.

As we left the courtroom, Clare’s attorney intercepted us in the hallway.

“Mrs. Brennan,” he said smoothly. “A word.”

Catherine eyed him.

“Make it quick,” she said.

He gestured toward a quiet corner.

“My client is willing to negotiate,” he said.

“There’s nothing to negotiate,” Catherine replied.

“Hear me out,” he said. “Ms. Cuban is willing to return all transferred property, void the power-of-attorney documents, and pay for Mr. Cuban’s medical care going forward. In exchange, Mrs. Cuban drops all criminal complaints and signs a nondisclosure agreement.”

“Absolutely not,” I said before Catherine could speak.

“Mrs. Cuban,” the attorney said, “a trial could take years. It will be expensive, emotionally draining. You might not win. Criminal conviction requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt.”

“I have proof,” I said.

“You have mostly circumstantial evidence,” he said. “My client maintains her innocence. She was trying to help her parents and now finds herself unfairly vilified. I’m offering you stability and closure.”

I stepped closer.

“Your client poisoned my husband for four years,” I said quietly. “She stole from us. She tried to have me declared incompetent. And you think I’ll let her walk away because it’s convenient? No deal.”

Back at the house, sheriff’s deputies collected the pill organizer that same afternoon.

“We’ll send these to the lab,” one of them said. “It may take a week, maybe longer.”

That night, James arrived from Chicago.

He looked exhausted, older than his thirty-eight years, with the kind of defeated posture I’d never seen in him before.

“Mom,” he said as soon as he stepped into the kitchen. “I don’t know what to believe anymore.”

“Then don’t believe anyone,” I said. “Look at the evidence.”

We sat at the kitchen table. I pushed the folder toward him.

He read.

The toxicology report. The legal documents. The forged signatures. Dr. Hartley’s statement. Dr. Santos’s conclusions.

I watched his face as understanding dawned slowly, followed by horror.

“She really did it,” he whispered.

“Yes,” I said.

“She drugged Dad,” he said. “And stole from you. And I…”

He shut his eyes.

“I helped her,” he said. “I witnessed documents. I vouched for her. I told you she was the responsible one.”

“You were manipulated,” I said. “We all were.”

“How do I fix this?” he asked.

“You testify,” I said. “You tell the truth about what she had you sign. You stop protecting her.”

He nodded slowly.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay. I’ll do it.”

The week crawled by.

Steven continued to improve. Some days were better than others, but the overall trajectory was clear. The fog was lifting.

He remembered our wedding day in the little country church, the year we bought the farm, the births of our children. He remembered the blizzard of ’78 and the drought of ’88 and the year the tornado had skipped our property by a quarter mile.

He cried when I told him what Clare had done.

“My own daughter,” he kept saying. “How could she?”

I had no answer.

Friday afternoon, Catherine called.

“The lab results are back,” she said. “The pills in the organizer Clare prepared contain dazipam mixed in with the legitimate medications. We have her.”

I closed my eyes.

“What happens now?” I asked.

“Now the county attorney files criminal charges,” she said. “Elder abuse, fraud, possibly attempted theft. Your daughter will be arrested.”

“When?” I asked.

“Soon,” she said. “Very soon.”

That night, my phone rang.

Clare.

I almost let it go to voicemail.

But after everything, some part of me still answered.

“Mom,” she said. Her voice was raw. “Please. We need to talk.”

“There’s nothing to say,” I replied.

“There’s everything to say,” she insisted. I could hear her breathing fast. “I made mistakes. I got scared about money and I made terrible decisions. But I never meant to hurt Dad. I never wanted—”

“You poisoned him for four years,” I said flatly.

“I was trying to slow him down,” she said desperately. “To keep him safe. To—”

“You were trying to steal from us,” I said. “And when I caught you, you tried to have me declared incompetent.”

Silence.

“I’m your daughter,” she whispered. “Doesn’t that mean anything?”

“You stopped being my daughter the moment you put those drugs in your father’s medication,” I said.

“Mom, please,” she said.

I hung up.

Two days later, Clare was arrested.

The local news covered it.

Prominent Des Moines fraud examiner charged with elder abuse and financial exploitation.

Her mugshot appeared on the evening report, her hair disheveled, eyes red from crying, nothing like the polished professional image she’d cultivated online.

I felt no satisfaction.

Just a deep, bone-deep sadness.

The preliminary hearing reconvened with the lab results in hand.

This time, with the pill organizer evidence directly tying Clare to the drugging, her attorneys had no clean defense.

Judge Winters ruled that there was probable cause for criminal prosecution.

Clare was released on bail with strict conditions: no contact with Steven or with me, no access to any Cuban family properties or accounts.

Catherine filed separate civil suits to undo everything Clare had done—to void the fraudulent documents, to restore title to the property, to seek restitution for legal and medical costs.

It would take months to untangle.

Maybe years.

But we had won the most urgent battle.

The daughter I had raised was gone.

Whether she had never been who I thought she was, or whether greed and desperation had slowly twisted her into someone unrecognizable, I didn’t know.

Either way, I knew this: I would never forgive her. Not then.

And I would never forget what I’d learned—that the greatest dangers sometimes come from within our own families, dressed in concern and wearing the face of love.

Spring arrived slowly in Iowa that year.

The winter was reluctant to release its grip on the land. Snowmelt turned the gravel roads to mud and left the fields slick and dark.

I watched from the farmhouse porch as ice retreated from the ditches, revealing black earth that would soon be ready for planting.

Steven sat beside me in his rocking chair, a blanket over his knees. His eyes were clear and focused in ways they hadn’t been in four years.

“The soil looks good this year,” he said.

“Should be a strong growing season.”

“It should,” I agreed.

“Think Harold will help with the planting?” he asked. “My coordination isn’t what it used to be.”

“Already arranged,” I said. “He’s bringing his son.”

Steven reached over and took my hand.

“I’m sorry, Margaret,” he said quietly.

“For what?” I asked.

“For not seeing what was happening,” he said. “For being so easy to fool.”

“You weren’t fooled,” I said. “You were drugged. There’s a difference. We both were fooled in our own ways. Clare was very convincing.”

Six months passed between Clare’s arrest and the date set for her criminal trial.

Her lawyers filed continuances, trying to delay the inevitable, but the civil cases moved faster.

Judge Winters voided all fraudulent documents, restored the property fully to Steven and me, and ordered Clare to pay restitution for legal fees and medical expenses.

She lost her job when the charges became public. Her professional reputation, built on detecting fraud, collapsed under the weight of her own fraudulent actions.

I saw her only once after that.

It was at a required mediation session in a small conference room at the courthouse. She looked thinner, older, her designer wardrobe replaced by an off-the-rack suit that didn’t fit quite right.

She wouldn’t meet my eyes at first.

During a break, she approached me in the hallway.

“Mom,” she whispered, “I’m so sorry. I know you can’t forgive me. I don’t expect you to. But I need you to know… I never meant for it to go this far. It started small. Just borrowing a little money. Then I couldn’t stop. I got desperate.”

“Stop,” I said, holding up a hand.

“I don’t want your explanations,” I said. “I don’t want your apologies. I want you to face the consequences of what you did.”

“I am facing them,” she said. “I’ve lost everything.”

“You lost nothing you deserved to keep,” I replied.

That had been three months before the trial date.

We hadn’t spoken since.

James visited more frequently now.

Guilt drove him, though he never said the word.

He’d testified at hearings about the documents he’d witnessed without reading, about the trust he’d placed in his sister.

The prosecutor assured him he wouldn’t face charges. He’d been a victim too, however unwitting.

“Mom,” he said during one visit, standing on the back porch with his hands in his pockets, staring across the fields, “I should have been here more. If I’d paid attention instead of just leaving everything to Clare—”

“You trusted your sister,” I said. “That’s not a crime. It was a mistake.”

“A big one,” he said.

“Yes,” I replied. “But you’re learning from it. That’s what matters.”

Dr. Hartley had become an unexpected ally.

Once freed from Clare’s threats, he had been tireless in documenting Steven’s recovery. He provided expert testimony about drug-induced cognitive impairment, connected us with specialists in Iowa City who could help with Steven’s rehabilitation, and attended follow-up appointments himself when he could.

“Your husband is remarkable,” he said at one appointment. “Most patients who’ve been on benzodiazepines this long show significant permanent impairment. But Steven is recovering cognitive function I wouldn’t have thought possible.”

“He’s stubborn,” I said. “Always has been.”

Dr. Hartley smiled.

“That stubbornness is serving him well,” he said. “His memory isn’t perfect. There are gaps that may never fill in, especially from the period when he was most heavily medicated. But he’s oriented, rational, capable of independent decision-making. If anyone ever questions his competency again, I’ll testify for him.”

The community’s response surprised me.

After the initial rush of gossip and whispered speculation at the diner and the church potlucks, Milbrook did what small towns often do—they closed ranks around their own.